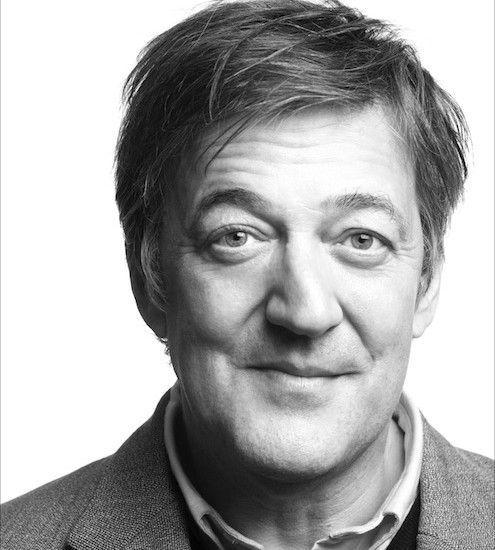

I was so nearly an American. It was that close. In the mid-1950s my father was offered a job at Princeton University – something to do with the emerging science of semiconductors. One of the reasons he turned it down was that he didn’t think he liked the idea of his children growing up as Americans. I was born, therefore, not in NJ but in NW3.

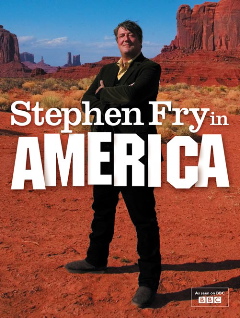

An excerpt from my book Stephen Fry in America

Stephen Fry in America on BBC 1 from Sunday 12th October @ 9.00pm

I was ten when my mother made me a present of this momentous information. The very second she did so, Steve was born.

Steve looked exactly like me, same height, weight and hair colour. In fact, until we opened our mouths, it was almost impossible to distinguish one from the other. Steve’s voice had the clear, penetrating, high-up-in-the-head twang of American. He called Mummy ‘Mom’, he used words like ‘swell’, ‘cute’ and ‘darn’. There were detectable differences in behaviour too. He spread jam (which he called jelly) on his (smooth, not crunchy) peanut butter sandwiches, he wore jeans, t-shirts and basketball sneakers rather than grey shorts, Airtex shirts and black plimsolls. He had far more money for sweets, which he called candy, than Stephen ever did. Steve was confident almost to the point of rudeness, unlike Stephen who veered unconvincingly between shyness and showing off. If I am honest I have to confess that Stephen was slightly afraid of Steve.

As they grew up, the pair continued to live their separate, unconnected lives. Stephen developed a mania for listening to records of old music hall and radio comedy stars, watching cricket, reading poetry and novels, becoming hooked on Keats and Dickens, Sherlock Holmes and P. G. Wodehouse and riding around the countryside on a moped. Steve listened to blues and rock and roll, had all of Bob Dylan’s albums, collected baseball cards, went to movie theatres three times a week and drove his own car.

Stephen still thinks about Steve and wonders how he is getting along these days. After all, the two of them are genetically identical. It is only natural to speculate on the fate of a long-lost identical twin. Has he grown even plumper than Stephen or does he work out in the gym? Is he in the TV and movie business too? Does he write? Is he ‘quintessentially American’ the way Stephen is often charged with being ‘quintessentially English’?

All these questions are intriguing but impossible to settle. If you are British, dear reader, then I dare say you too might have been born American had your ancestral circumstances veered a little in their course. What is your long-lost nonexistent identical twin up to?

Most people who are obsessed by America are fascinated by the physical – the cars, the music, the movies, the clothes, the gadgets, the sport, the cities, the landscape and the landmarks. I am interested in all of those, of course I am, but I (perhaps because of my father’s decision) am interested in something more. I have always wanted to get right under the skin of American life. To know what it really is to be American, to have grown up and been schooled as an American; to work and play as an American; to romance, labour, succeed, fail, feud, fight, vote, shop, drift, dream and drop out as an American; to grow ill and grow old as an American.

For years then, I have harboured deep within me the desire to make a series of documentary films about ‘the real’ America. Not the usual road movies in a Mustang and certainly not the kind of films where minority maniacs are trapped into making exhibitions of themselves. It is easy enough to find Americans to sneer at if you look hard enough, just as it is easy to find ludicrous and lunatic Britons to sneer at. Without the intention of fawning and flattering then, I did want to make an honest film about America, an unashamed love letter to its physical beauty and a film that allowed Americans to reveal themselves in all their variety.

I have often felt a hot flare of shame inside me when I listen to my fellow Britons casually jeering at the perceived depth of American ignorance, American crassness, American isolationism, American materialism, American lack of irony and American vulgarity. Aside from the sheer rudeness of such open and unapologetic mockery, it seems to me to reveal very little about America and a great deal about the rather feeble need of some Britons to feel superior. All right, they seem to be saying, we no longer have an Empire, power, prestige or respect in the world, but we do have ‘taste’ and ‘subtlety’ and ‘broad general knowledge’, unlike those poor Yanks.

What silly, self-deluding rubbish! What dreadfully small-minded stupidity! Such Britons hug themselves with the thought that they are more cosmopolitan and sophisticated than Americans because they think they know more about geography and world culture, as if firstly being cosmopolitan and sophisticated can be scored in a quiz and as if secondly (and much more importantly) being cosmopolitan and sophisticated is in any way desirable or admirable to begin with. Sophistication is not a moral quality, nor is it a criterion by which one would choose one’s friends. Why do we like people? Because they are knowledgeable, cosmopolitan and sophisticated? No, because they are charming, kind, considerate, exciting to be with, amusing … there is a long list, but knowing what the capital of Kazakhstan is will not be on it.

The truth is, we are offended by the clear fact that so many Americans know and care so very little about us. How dare they not know who our Prime Minister is, or be so indifferent as to believe that Wales is an island off the coast of Scotland? We are quite literally not on the map as far as they are concerned and that hurts. They can get along without us, it seems, a lot better than we can get along without them and how can that not be galling to our pride? Thus we (or some of us) react with the superiority and conceit characteristic of people who have been made to feel deeply inferior.

So I wanted to make an American series which was not about how amusingly unironic and ignorant Americans are, nor about religious nuts and gun-toting militiamen, but one which tried to penetrate everyday American life at many levels and across the whole United States. What sort of a design should such a series have? What sort of a structure and itinerary? It is a big country the United States…

The United States! America’s full name held the clue all along, for America, it has often been said, is not one country, but fifty. If I wanted to avoid all the clichés, all the cheap shots and stereotypes and really see what America was, then why not make a series about those fifty countries, the actual states themselves? It is all very well to talk about living and dying, hoping and dreaming, loving and loathing ‘as an American’, but what does that mean when America is divided into such distinct and diverse parcels? To live and die as a Floridian is surely very different from living and dying as a Minnesotan? The experience of hoping and dreaming as an Arizonan cannot have much in common with that of hoping and dreaming as a Rhode Islander, can it?

So, to film in every state. I had a structure and a purpose. But how would I get about? I often drive around in a London taxi. The traditional black cab is good and roomy for filming in and perhaps the sight of one braving the canyons, deserts and interstate highways of America could become a happy signature image for the whole journey. A black cab it would be.

There is no right tempo for a project like this. The whole thing could be achieved in two weeks by someone who just wanted to tick off the states like a train-spotter, or it could be done over the course of years, with great time and attention given to the almost infinite social, political, cultural and physical nuances of each state. The pace at which my taxi and I zipped along provided me not with definitive portraits but with multiple snapshots of experience, which I hope when taken together will cause a bigger picture of the country and its fifty constituent parts to emerge.

The overwhelming majority of Americans I met on my journey were kind, courteous, honourable and hospitable beyond expectation. Such striking levels of warmth, politeness and consideration were encountered not just in those I was meeting for on-camera interview, they were to be found in the ordinary Americans I met in the filling-stations, restaurants, hotels and shops too.

If I were to run out of petrol in the middle of the night I would feel more confident about knocking on the door of an American home than one in any other country I know – including my own. The friendly welcome, the generosity, the helpfulness of Americans – especially, I ought to say, in the South and Midwest – is as good a reason to visit as the scenery. Yes, Americans are terrible drivers (endlessly weaving between lanes while on the phone, bullying their way through if they drive a big vehicle, no waves of thanks or acknowledgement, no letting other cars into traffic), yes they have no idea what cheese or bread can be and yes, strip malls, TV commercials and talk radio are gratingly dreadful. But weighing the good, the kind, the original, the enchanting, the breathtaking, the hilarious and the lovable against the bad, the cruel, the banal, the ugly, the crass, the silly and the monstrous, I see the scales coming down towards the good every time .

There is one phrase I probably heard more than any other on my travels: Only in America!

If you were to hear a Briton say ‘Tch! only in Britain, eh?’ it would probably refer to something that was either predictable, miserable, oppressive, dull, bureaucratic, queuey, damp, spoil-sporty or incompetent – or a mixture of all of those. ‘Only in America!’ on the other hand, always refers to something shocking, amazing, eccentric, wild, weird or unpredictable. Americans are constantly being surprised by their own country. Britons are constantly having their worst fears confirmed about theirs. This seems to be one of the major differences between us.

VERMONT, Vermont, how beautiful you are.

Not the absolute last place in which you would imagine Rudyard Kipling writing ‘Gunga Din’ and The Jungle Book, but surely not the first, either. Yet he did. And ‘Mandalay’ too, ‘where the flyin’-fishes play’, in Battleboro, VT, the home of his American wife, Carrie.

I reckon that if you ask the average American what they know of Vermont, the first thing they will mention is maple syrup. The sugar maple is the ‘State Tree’ of Vermont – it is also more or less the state industry. The maple brings tourists who come to marvel at the blazing colours of the autumn leaves and it brings cash dollars in the form of the unctuous, faintly metallic syrup that Americans like to pour all over their breakfast, on waffles and pancakes, but on bacon too. Sounds alarming to English ears, but actually it is rather delicious. Like crack, crystal meth and Chocolate HobNobs, one nibble and you’re hooked for life.

I am a little late for catching the legendary beauty of Vermont’s fall. The best days for ‘leaf peeping’ have gone and the time of maple tapping is yet to come.

What else does Vermont have to offer? Not a thrusting metropolis, that is for sure. Montpelier is the smallest of all the state capitals, with a population of barely eight thousand. The nickname Green Mountain State suggests pastureland, and pasture suggests cows and sheep and goats, and cows and sheep and goats suggest dairy produce – milk, cream and cheese. There is a bastard concoction that dares to call itself ‘Vermont Cheddar’ but that we will ignore, presenting it with the coldest of British shoulders. No, I am in search of a product altogether more desirable, a world more indulgent and disgraceful, wholly addictive and dreadful and proudly American: it is the prospect of this which has me hurtling northwest with the intense concentration and merciless swiftness of a shark streaking towards blood in the water. Except that sharks don’t drool and shout ‘Come to mama!’

It was in 1978 that the two sainted hippies, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield opened their first ice-cream parlour in Burlington, Vermont’s largest town. After many adventures, tribulations and law-suits against Häagen-Dazs they established themselves as just about the best known brand in ice-cream.

The factory in Waterbury, VT, is about thirty miles southeast of Burlington and constitutes Vermont’s single biggest tourist attraction. The moment I arrive I feel like Veruca Salt standing at the gates of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. With golden ticket clutched in fist I want it and I want it now.

I am to be given the freedom of the ingredients cabinet, a chance to mix my own flavour. This is an honour rarely bestowed. It is as if Château Margaux asked me to blend their cabernet sauvignon and merlot for this year’s vintage. Well, all right, it’s nothing whatever like that, but it is a great honour nonetheless.

‘Welcome, Stephen, we’re very excited that you’re here!’ says Sean, the flavorologist. ‘But if you’re gonna mix like a pro, you’d better dress like a pro.’

He hands me a white lab coat while I ponder the task before me.

The base, I decide, should be of good vanilla-bean ice-cream, nothing more fancy than that. To hand are spatulas, spoons and little pots and bags of semi-frozen ingredients: cookie dough, biscuity substances, chocolate in the shape of a cow and so forth. I try to stay calm. I mustn’t be too childish about this, what little dignity I have left is at stake. The temptation to produce a pink confection filled with marshmallows, strawberries and cake mix is strong, but I feel the need to fly the flag for British style and discretion. I find an ingredient called English toffee and swirl it into the vanilla base. Good. Not the kind of hard black toffees Kensington nannies gave children in their prams to keep them quiet while they kissed the footman, but a good start. To this promising base I add chocolate fudge, a gloopy substance that freezes when added to the ice-cream, like a lava flow meeting water. A granulated texture is added with which I feel well pleased.

Very fine – strong, adult, not too sweet, but there’s something missing … I rootle and scrabble, searching for the magic extra ingredient that will transform my mixture into a true flavour, my rough prototype into a working masterpiece. The clock is ticking, for a tour party is about to come in at any moment and I am to feed them and then stand with bowed head to receive their judgement.

Just as I am about to give up and offer my acceptable but now to my mind rather lame decoction my fingers curl around a bag of knobbly somethings. I have found it! It adds crunch, a hint of sophisticated bitterness and a rich musty, nutty centre around which the other flavours can play their unctuous, toffee-like, chocolaty games. Walnuts! I stir them in with my spatula and Sean helps me transfer the giant mixture into small tourist-sized tubs. This is done by squeezing a kind of piping bag. Within seconds I have lost all feeling in my hands.

‘It’s very cold,’ I observe.

‘Many are cold,’ says Sean, ‘but few are frozen.’

Before I have time to throw something at him, the tour party enters.

‘Welcome everybody,’ beams Sean. ‘This is a special occasion. You will be trying a new flavour, mixed by our Guest Flavorist, here. His invention is called …?’

‘Er … I … that is … um …’

‘… is called “Even Stephens”!’ extemporises Sean happily.

I stand meekly, submissively, hopefully while the tourists surge forward to begin the tasting. Despite my humble demeanour, I know, I really know that I have struck gold. There have not been many moments in my life when I have been quite so sure of success. But here, I am convinced, is a perfect blend of flavours.

The tourists agree. Once the filming stops and the camera crew have dived in too there is nothing left of Even Stephens but my memory of a solid-gold vanilla-based triumph.

Stephen, you created an ice-cream flavour. And it was good. Now you may rest.

A TENNESSEE BOLTING HORSE

Georgia: Outside the Spanish moss profusely drips, as it should, from the live oaks and distant cypresses; all is as it ought to be at a plantation house in the Deep South. Except that I am expected to get on a horse.

Blackwater has a celebrated (apparently) stable of Tennessee Walking Horses, a breed of animal unfamiliar to me.

‘Oh they are so gentle and docile and sweet!’ My hosts, with whom I have come to spend Thanksgiving, tell me. ‘Docile’ rhymes with ‘fossil’ in American, which makes it sound even gentler. ‘You will adore them!’

‘

Yes, but they won’t adore me,’ I whine.

‘Nonsense! They are the kindest, calmest horses in the whole wide world. You’ll see.’

We go round to the stables where a large horse called Shadow is being saddled for me.

‘Look,’ I try to explain, ‘for some reason horses really, really don’t like me. No matter how calm and friendly I am they…’

‘Nonsense!’ they all giggle.

I step up from a block and just manage to get my feet in the stirrups before the sweetest, gentlest, most docile horse in the whole wide world screams, bucks and bolts. The family are all so astonished it takes them some little while to realise what has happened. A ‘some little while’ that is filled by me shouting ‘Whoa!’ and pulling as hard on the reins as I dare as below me a ton of mad jumping flesh gathers its hindquarters and prepares to charge a wooden fence. A last desperate yank on the lines and the crazed beast slows down enough to give the others time to catch up and grab it.

Naturally everybody thinks this is hilarious.

‘Well he’s never done that before…’

‘I declare!’

‘Who’d a thunk it?’

‘I should have made it clearer,’ I say. ‘Every time I have ever got on a horse it has ended with the remark you have just made: “He’s never done that before!” “But Snowflake is usually so calm…” There’s something about me and horses. Well. Make the most of the comedy, because that is the last time I shall ever, ever be seen on the back of a horse for the rest of my natural life.’

THE BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES

The judicial and penal systems of the South have always had a quality of their own. Cinema, literature, music and folklore have long revelled in the special cruelties and indignities of crime and punishment, Southern style.

Many years ago, Alabama’s state legislature brought into being in the capital, Montgomery, an institution called the Board of Pardons and Paroles whose job it is to hear both sides of an appeal for parole petitions. By both sides I mean that both the representatives of the convicts and the representatives of their victims get the chance to speak.

I am here to meet three members of the board, Robert Longshore, William Wynne and VeLinda Weatherley. They sit at their long bench, the seal of their office on the wall behind them, exuding Southern charm, courtesy and authority. I cannot believe that any equivalent British institution (were there such a thing) would ever allow a film crew to come poke around their proceedings with so little supervision or bureaucratic impediment. Mr Longshore explains to me in a drawl of stupendous charm that the pardons were the most enjoyable part of their work: as a rule these take the form of applications from criminals long since released who needs a pardon in order to be able to vote or own a gun. Paroles however are an entirely different matter. This is where the pain of crime comes home; this is where the wisdom of Solomon itself cannot guarantee to bring about a happy outcome.

On either side of the back of the tribunal space, which is laid out not unlike a courtroom, there is a door. Each door leads to a waiting room, one for parole petitioners, the other for families and representatives of the victims.

After a few straightforward cases of pardoning, a parole case begins. A family shuffles through the victims’ door. A late-middle-aged woman is so tearful she has to be supported. With them is a pale young white girl who works for an organisation called Victims of Crime and Leniency (VOCAL) who automatically, whatever the circumstances, always support the victims and oppose parole, whatever the case. Their default position is never to favour early release. For any prisoner. Ever.

Through the other door shuffles another, equally distressed family. The young man whose case for parole they are making is not present. The prisoners themselves never are, only their families and occasionally (if they have money, which is rare) their lawyers.

A story emerges that is so sad, so squalid and so unfair that within minutes I (and many in the court, including some of the camera crew) are wiping away tears.

The prisoner is twenty-seven years old and has been in jail since he was seventeen on a charge of manslaughter. He was given a twenty-year sentence. He had been horsing around with a gun when he had shot his fifteen-year-old friend in the head. Apparently it was all part of some game that had got out of hand. No one in the original sentencing court and no one here at the Board believed that it was anything more than a terrible accident. The two boys, the two families, had been friends, but the mother of the dead boy will not hear of clemency for the imprisoned boy.

She stands up now, a central casting picture of tottering maternal woe. She wails, she screams, she cannot put into words her continuing upset and has to be led from the proceedings sobbing and keening. The woman from VOCAL speaks for her. The boy in prison is still alive. He has only served half his sentence. The court wanted him in prison for twenty years, the board should respect that. He should not be allowed even to apply again for another five years, the maximum length.

The family of the imprisoned boy make their case. Their son has served exemplary time: not one punishment for infractions of prison rules. He has learned new trades and has passed examinations. He was never a criminal. What good can be done by keeping him locked up? It was an accident after all, a terrible accident.

To me it is, as they say in America, a slam dunk. Surely the boy must get his parole?

He does not. It is not the Board’s duty to look into the rights or wrongs of sentencing, only to respond to the case as it is. This boy’s first appeal will not be accepted, says Mr Longshore, it is too early.

However his good behaviour is noted and he is therefore given the right to appeal in four years. Another four years of hard time ahead of him.

I am astonished. Astonished that the family of the slain boy should want such revenge against the friend who so tragically took a game too far. It could have been their son who shot the other boy, had fate dealt different cards. Surely they should embrace the boy who killed their son, wouldn’t that help them heal? I am astonished too by the callousness of the woman from VOCAL and her absolute lack of sympathy for the killer. I am no Christian, but I know that the founder of her religion would feel differently. Is it not possible to care for both victim and perpetrator?

I bid farewell to the Board and to Alabama, mixed feelings churning in my breast. Rarely have I met people more charming, more polite and more hospitable. The boy who pumps the gas in the forecourt really does call you ‘sir’, the receptionist at the hotel has a wide smile when she asks ‘how y’all doing?’ and the smile is warm and real. But this is not a place where I would ever want to be poor or independent-spirited, and certainly not a place where I would want to fall foul of the law.

SPY GAMES

Las Vegas, Nevada: I sit in my slate grey and chromium hotel suite fretting about the fact that I haven’t found a way to turn off its real-flame fireplace, but European eco-guilt has as much place in Las Vegas as a stripper at a synod. Less.

The doorbell rings and within seconds I am embroiled in a nightmare of identity, treachery and betrayal. She calls herself Trixie. She wears a raincoat and a fedora. She tells me that I have been selected to act as a double-agent, a mole: my mission is to infiltrate myself within … well, to be perfectly honest with you, quite what I have to infiltrate myself into is for the moment beyond me. Dark powers working against the common good have conspired, that much is clear. The forces of good must be marshalled and the marshalling place is somewhere, it seems, on Howard Hughes Parkway. I have five minutes to get there. Your country needs you.

‘Britain?’

‘America!’ whispers Trixie.

‘Ah.’

‘Remember. At each place you visit there will be a contact. You must give them each one of these tokens. The others cannot know. You must keep your double-agent status secret from them.’

‘The others?’

Trixie and I zip down to the rendezvous in the taxi. I have to let her out before I meet the others, for they must not know that I have been contacted by her. The others, it turns out, are the Chippendales. Yes, the bow-tied male stripping combo that has for years delighted hen nights and Christmas parties the world over.

I am soon plunged into the guts of this ‘Spy Game’. From first to last I have no idea what is going on, but some quality of American-ness seems to allow the Chippendales to be absolutely clear about the whole proceeding. They accept their spy packs and cell phones and cameras as if they do this every day.

Spy games have become all the rage in Las Vegas. They are a structured, if expensive, way of seeing the town, and companies also use them for team-building exercises and the like. One is sent from venue to venue, mostly via the city’s monorail. From Caesar’s Palace to the Mirage, from the MGM Grand to the Flamingo we flit, meeting ‘contacts’ – who turn out to be obvious rain-coated, sun-glassed spooks. I manage to offload two of my mole-tokens before the smartest and most mouthy Chippendale, the ‘team-leader’, stops me, bids me empty my pockets and exposes me to all as the mole. Naturally I change sides immediately and am now a triple-agent.

It is all most confusing, but by the end of the afternoon I at least know Las Vegas better than I ever could have done otherwise.

MORMON CALENDAR BOYS

The unique moral outlook of Las Vegas seem somehow to have penetrated even the fastnesses of the Church of Latter Day Saints. The morning after my adventures in espionage, I arrive at a photo studio somewhere off the Strip to find myself surrounded by semi-naked young men whose more than ordinarily sparkling eyes, unblemished skin, gleaming teeth and air of sexless perfection tell me that they are Mormons, members of a church that forswears sex before marriage and stimulants or narcotics of any kind, from caffeine to nicotine and cocaine. These are all good Mormon boys who have done their ‘missionary work’, in other words they have travelled within America, or beyond, wearing white shirts and dark suits and spreading the word of Mormon. This is the second year of their (strictly topless and genital-free) calendar. It raises money for charity and seems to have won the reluctant acceptance of the Church Elders back in Salt Lake City.

I chat to Cody, a personable nineteen-year-old who is happy to discuss any part of his religion to me. He is surprised and pleased, I think, to learn that I do not find his faith particularly absurd, in the way many mainstream Christians do. I forebear telling him that the reason I do not find Mormonism especially ridiculous is because I find all pretend invisible friends, Special Books and their rules equally ridiculous. Mormon ideas about realms of crystal rebirthing and special underpants are no weirder than the enforcing of wigs and woollen tights on orthodox Jewish women or laws and dogmas about burkhas and Virgin Births. The religion of the Latter Day Saints is not deserving of especial contempt simply because it is newer. It is as barmy as the rest and I cheerfully treat it as such. It has the same impertinent views concerning women and gays, of course, but Cody is clearly embarrassed about this and says with a touch of defensiveness, ‘We aren’t as bigoted as some fundamental Christians.’ Mm. Yes. Well. I bid my farewells and head for Reno and some good old-fashioned hookers.

© Stephen Fry 2008

Stephen Fry in America

Stephen Fry in America on BBC 1 from Sunday October 12th @ 9.00pm