The Spectator Lecture, Royal Geographical Society, presented in London 30th April 2009

Here we are. Gathered together in the very lecture theatre where Henry Morton Stanley once told an enraptured world of his momentous meeting with Dr. Livingstone. Charles Darwin was a member and gave talks in this same hall. Sir Richard Burton lectured here and John Hanning Speke … spoke. Shackleton and Hillary displayed their intimate frostbite scars to a spellbound RGS audience. Explorers, adventurers and navigators have been coming here for the best part of 180 years to tell of their discoveries. If only at school, geography teachers, surely the most scoffed and pilloried class of pedagogue there is, if only they had concentrated less on rift valleys, trig points and the major exports of Indonesia and more on the fact that Geography could promise a classy royal society with the sexiest lecture theatre in the land – if only they had done that, then maybe cheap stand-up comedians and lazy cultural commentators would be less routinely scornful of geography teachers as a class and geography itself as a discipline, which is one I rather unfashionably enjoyed when I was young. Don’t ask me why. Actually, now that I think of it, one reason for me to be fond of the subject was the circumstance that in my prep school geography room there were piles and piles of shiny yellow National Geographic Magazines available for skimming through. These, with their glossy advertisements for Chesterfield cigarettes, Cadillac sedans and Dimple whisky, gave me my first view outside television of what America might be like. But there was another reason religiously to scan the magazines…

National Geographic, before it became a ‘brand’ best known for an imbecilic and embarrassing suite of digital TV channels, was – thanks to its anthropological coverage in a pre-internet, pre-channel 4, pre-top shelf age – the only place where a curious boy could look at full colour pictures of naked people. For that alone it deserves the thanks of generations. One did get the false impression that many peoples of the world had protuberances shaped exactly like a gourd, but never mind.

National Geographic made films too, and at my school these would be run through an old Bell and Howell projector by the geography masters to keep us quiet and to give them time to beetle off and pursue their amorous liaisons with matron or the whisky bottle, depending on which teacher it was. ‘Fry, you’re in charge,’ they would never say on their way out. But what strange films they left us to watch. I seem to recall that the subjects were usually logging in Oregon, the life cycle of the beaver or the excitements to be found in the National Parks of Montana and Wyoming. Very blue skies, lots of spruce, larch and pine and plenty of plaid shirtings. The unreliable speed of that hot and dusty old Bell and Howell rendered the soundtrack and its music flat then sharp then flat again in rolling waves of discord, but it was the commentators that gave me raptures with their magisterially rich and rolling American rhetoric. What a peculiar way with language they had, employing poetical tricks that had been out of date a hundred years earlier. My favourite was the ‘be-’ game. If a word usually began with the prefix ‘be-‘ it was taken off . Thus ‘beneath’ became ‘neath’ and so on. But the ‘be’ of ‘beneath’ wasn’t simply thrown away. No no. It was recycled by adding it to words it had no business being anywhere near. Which would result in preposterous declamatory orotundities of this nature: “Neath the bedappled verdure of the mighty sequoia, sinks the bewestering sun,” and so forth. And what is the proper name for this rhetorical trope, also much deployed? It would start with the usual ‘be-‘ nonsense: “Neath becoppered skies bewends …” but then this “the silver ribbon of time that is the Colorado River.” The weird and senseless maze of metonym and metaphor that was National Geographic Speak in all its besplendour was a great influence on me, for where others had rock and roll music, I had language.

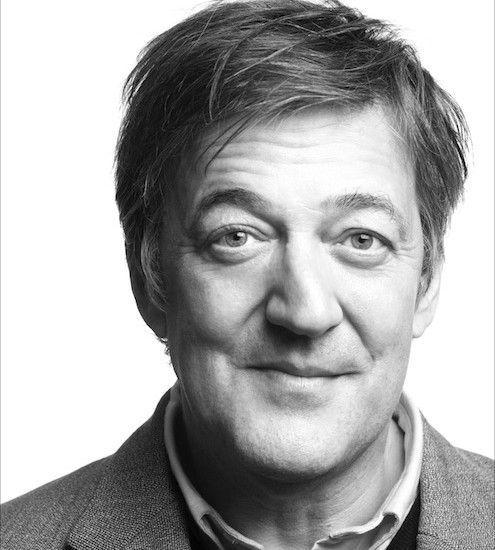

This is all a way of saying how pleased I am to be delivering this talk, this first ever Speccie Leccie, here in the temple, the palace, the very headquarters of geography. But it’s no good skirting the issue. This is not only an honour, it is also a great surprise. Not only to me, I would venture to suggest, but to the preponderance of Spectator readers around the land too. In fact not so much a surprise, more a deeply unpleasant shock. Acquit me of false modesty when I state that I take it as certain that when Mr. D’Ancona, the Spectator’s sappy young editor, announced to his readers (and I dare say to his staff) that he had chosen me to deliver the inaugural lecture there were many horrified screeches of startled disbelief and agonized howls of apoplectic protest. Surely persons such as I are exactly what the Spectator holds itself foursquare against? Am I not just about the Platonic form, paradigm and pattern card of everything the magazine was put on this earth to dispraise, damn and destroy? I am a crew member of that ship of fools, the sneering liberal elite, a cheerleader of the chattering classes, a loathsome Labour luvvie, a champagne socialist a – goddammit – a celebrity, a twittering celebrity dripping with the sickening syrup of popular culture, political correctness and nauseating kneejerk liberalism that is the leading symptom if not the primary cause of our national decay. It is as if all nature conspired to make a living suppurating mass, a walking purulent bolus compounded of all the poison and pus that oozes and weeps from the sores of today’s Britain and gave it legs, life and a name. Stephen Fry. Lo. Gaze upon him. Know your enemy. And it is he, he of all people, who has been chosen to give the inaugural Spectator Lecture. Eheu fugaces: o tempora o mores. Ichabod. The glory is departed.

I exaggerate, the kinder of you may say. But I repeat, without rancour if not entirely without rue, that I know this to be the case, because I know my country. I know the tribes of Britain. I have seen fifty summers, and during the course of my life I have long been fascinated this side obsession by the caste, class and clans of my people. We may not wear physical gourds on our intimate persons, but we certainly wear notional ones, and our war dances, face paints, initiation rituals, fetishes, tattoos, taboos and blood feuds are no less fascinating to the anthropologist than those of the tribespeople of Papua New Guinea.

But as Kipling wrote and Billy Bragg repeated, what do they of England know that only England know? My travels in the last year or so have taken me to Mexico, Brazil, Malaysia, Madagascar, Uganda, Kenya, New Zealand, Indonesia and, more importantly for this occasion, to every one of the 50 states of the USA. I was in America for the run up to the presidential election, but for the ballot itself I was in Kenya, the homeland of course of Barack Obama’s father. I asked a Kenyan with whom we were working whether he was pleased that America looked to be about to have its first black president, and one of Kenyan extraction at that? ‘Very pleased,’ he replied. ‘But you must remember Mr. Obama’s mother is of European extraction. If Barack Obama had stayed here and been elected as our leader, he could have become Kenya’s first white president.’

My love affair with America began – began where? Perhaps with the berolling bevalleys of betwattled absurdity that were the National Geographic films, perhaps with the lifestyle advertisements in those National Geographic magazines, perhaps with Wagon Train, Rawhide and The Lone Ranger or with Bewitched, Dick van Dyke and Lucille Ball on television. Not, with rock and roll I’m afraid. Elvis never did much for me, apostasy as I’m sure it is to confess. Nor did Blues or Jazz or R&B at that time. Certainly not Steve McQueen. I have always disliked cool. For me it is simply another word for cold. But Spenser Tracey, James Stewart, Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Katherine Hepburn – they certainly helped me fall in love with America. Although to be honest gangsters, cowboys, dancers and movie stars weren’t, as they were for so many, the real pull. A major influence on me was P. G. Wodehouse. He adored America and ended his life a proud US citizen. He first went in Edwardian days when, as he later recalled, you could simply pop into a shipping line office in Cockspur Street, buy a ticket and be on the boat train to Southampton in an instant. No nonsense about passports and visas. Everything Wodehouse wrote about the energy, vivacity, warmth, welcome and excitement of America thrilled me and I vowed to go there myself as soon as I could. I little thought that one day I would have a Manhattan apartment of my own, a green card and even be made a Kentucky Colonel. It’s true. One doesn’t like to boast, but Steve Beshear, the Governor of the State – actually the Commonwealth of Kentucky – bestowed that rank upon me, uniquely in the gift of Kentucky, last year. Unlike Harland Sanders of Fried Chicken fame, who was accorded the same title, I don’t use it. But if you choose to call me Colonel Fry I shall certainly answer and with pride. But all this lay ahead of me in a future I could not possibly imagine.

I had American family too. Those from my mother’s side who survived the horrors of the holocaust went to Israel or America or both. All that is, except for my mother’s parents who chose to make their home here in England. American relations would descend into our drab early 60s British world of grey weather, grey trousers and grey attitudes dripping colourful slacks, pants and jackets, sparkling jewels, thrilling cameras, perfumed furs and expensive tchotchkes of all kinds. They brought these treasures to us in Pan-Am or TWA overnight bags or ‘grips’ that also contained thrilling trophies of their jet travel: miniature salt cellars and pepper pots, paper napkins bearing the airline’s crest and foil sachets that held moist lemon-scented cleansing squares, or ‘handy freshen-up wipettes’ of unimaginably exotic strangeness and wonder. Over these precious souvenirs my brother and I would fight like wild beasts. Back home in the states, as my Yankee cousins made clear by their astonishment at our conspicuous lack of them, they had ice machines, air conditioning, stereo sets and colour televisions. Damn it, in Britain even our TV was grey. In my eyes my American cousins were little short of gods: their basketball sneakers shamed my plimsolls, their t-shirts laughed at my short-sleeved air-tex and their Levi jeans made a blushing disgrace of my bagged corduroys. The details of suburban American living I think excited me more than the mythology of the West or of Chicago’s South Side or of the surfers of Santa Monica. I liked trying to understand what bake-offs, yard sales, drive-in movies and spelling bees were, what sophomores and semesters might be and what homecoming queens and commencement and proms and Spring Break and Elks and Shriners and pledge rings and trick or treat could possibly portend.

All this obsession might well have derived from the fact that I was so very nearly born an American myself. In the mid 1950s my father, a physicist fresh from Imperial College, was offered a job at Princeton University – something to do with the emerging science of semiconductors. One of the reasons he turned it down was that he didn’t think he liked the idea of his children growing up as Americans. This sprang not from a dislike of America so much as a disinclination, I must suppose, from having “Gee dad” directed at him over breakfast. Breakfast which would have been constituted of grahams or granola or creamed wheat or even hominy grits – the eggs would have been sunny side up or over easy and maple syrup would have been poured over Canadian bacon and link sausages: there would have been cream cheese. Not cream cheese, but cream cheese, that’s how they said it in America. There would have been stacks too of buckwheat buttermilk pancakes, waffles, bagels and blueberry muffins. There would have been fresh orange juice and Hershey’s chocolate milk and … but, no it was not to be. Thanks to my father’s decision I was born no t in America, but in England and my parents would be forever Papa and Mama or Father and Mother but never Dad and Mom and it was Force Wheat Flakes, Scott’s Porage Oats, boiled eggs and soldiers for brekker and the orange juice was prepared from frozen concentrate, just as our emotions, it seemed to me, also derived from frozen concentrate.

I was only told years later, when I was 10, about this opportunity my father had had to go to Princeton. This startling intelligence had quite an effect on me. I have written in the introduction to the book you lucky, lucky people have been presented with by the all-benevolent Spectator, I have written that the idea of having come so close to being American caused me to imagine a whole other self, the American I would have, should have become, a personage I dubbed Steve. I accorded Steve with almost magical powers and wealth. He could drive by the time he was 16, he wore Converse sneakers and Wrangler jeans, he ate hamburgers, whatever they were and drank cream sodas whatever they were from a bendy straw – even bendy straws were exotic in my country childhood. Only one place in Norwich had them. I grew up in a large house with gardeners, staff, a fireplace in every room and people to lay and light them, yet I felt like the most deprived child in the world compared to Steve. Steve was confident and happy and strong and secure in exactly the way that I was unconfident, unhappy, weak and insecure. He spoke in a sweet, lazy and sexy drawl. He was better looking, better nourished and better liked than I was. I longed to be him. He was American. I had fallen in love with America and could not wait to get there.

Of course falling in love with America almost always suggests falling in love with the idea of America, a phrase that makes little sense if you substitute the word ‘Britain’ for ‘America’ and suggest ‘the idea of Britain’. Britain does not present itself to the world or to its own citizens as an idea, an ongoing project, a work in progress in the way that America still so emphatically does. And I would not want you to think that my love of America meant contempt or estrangement from Britain. No one, I think, could accuse me of adopted American mannerisms, or being somehow unEnglish. Indeed if I had a gold sovereign for every time I have been told that I am ‘quintessentially English’ I would have enough gold sovereigns to stuff in a sock and knock the next person who told me that into violent unconsciousness…

For what is quintessential Englishness? Warm beer and the vicar on his bike on the way to a cricket match? Saturday night drinking and vomiting is surely more representative? Jade and Di worship? Club 18-30? The Garrick Club? Reality TV? Pub quizzes? Dr Who? Mean-spirited, hypocritical and opinionated newspaper columnists? Some people might say Agatha Christie and Winston Churchill are as British as you can get without falling over in a faint and yet both Churchill and Christie, as it happens, were half American.

So what is quintessentially American? Apple pie or Apple computers? Walmart or Wall Street? Trump Towers or Twin Towers? Jimmi Hendrix or Jimmy Stewart? Opportunity or opportunism? Small town courtesy or small-minded bigotry. Hearty milk and cookies or Harvey Milk and hookers. Blue collars, red necks, white supremacy or black power? The Simpsons or The Waltons, Family values or Family Guy, Holly Golightly or Hollywood, Penn State or the State Pen or Sean Penn, the right to life or the right to electrocute, capitalism or capital crimes, poncey dreams or Ponzi schemes, Nobel prize winners or ignoble price fixers, a country that can land men on the moon and yet has a majority who believe that angels walk amongst us – I suppose we could play this game of opposites for ever for I do not know a single thing that can be said about America whose reverse is not also true. It is a land of opportunity and yet there are more seventeen year old black youths in prison than in college. It is a land of freedom where in many states you can’t buy fireworks or alcohol or cross the street as a pedestrian where you please and where children’s books are banned and educational material suppressed if they do not square with some religious dogma or other. It is a land of church-going traditionalists and a land of freaks and fancies. A nation founded in revolution where radicalism is next to Satanism. A land of industry where indolence has created an epidemic of obesity whose walking examples, or waddling examples I should say, have to be seen to be believed. One country riven by a depth of mutual bipartisan enmity, loathing and distrust that threatens entirely to divide it into two and propel the nation into a new Civil War. However much Britain may be divided along tribal lines, it is as nothing when compared to America. The reciprocated antipathy is intense and seems irreconcilable. Did the election of Obama heal that fissure? Briefly seal it perhaps, but certainly not heal it. A hundred days later it all seems to be opening up again as wide as ever and anyone who watches Fox News will know that as far as President Obama’s political enemies are concerned the honeymoon was over before the garbled vows were out of the bridegroom’s mouth: the United States were soon disunited all over again.

But that is not my subject today. Just two days ago President Obama announced that he was aiming for a Federal science and research budget that would represent 3% of America’s output. I’ll quote him in full: “I believe it is not in our character, American character, to follow — but to lead. And it is time for us to lead once again. I am here today to set this goal: we will devote more than 3 percent of our GDP to research and development.” Heaven knows I couldn’t be more pleased to hear that. When he mentioned science in his inaugural address I cheered too. Those who cheer the opposite, those who cheer the sweeping back of the achievements of the enlightenment, those who believe they are doing god’s and the family’s work by defying relativism and re-asserting absolutism they may boo, but I do not. But let’s look at for me the most interesting part of the President’s statement.

This strikes, I think, at the heart of the juicy mixture of beguiling paradoxes, ambiguities and contradictions that distinguishes all things American, whether that mixture will emulsify or curdle is perhaps the question of our age. The title of my lecture is supposed to be America’s Place In The World (and I may as well confess here and now that Mr D’Ancona made it up, handed it to me and printed out the fliers before I had a chance to consider what I wanted to lecture on. But that’s fine. Easier to respond to a clear commission than to start from a blurred blankness). The US President has answered the question for me. America’s place in the world, it seems, is in the van. At the front. Leading, not following.

Well, in terms of international policy, peace-keeping, policing and global influence this may still be true. But I cannot speak to abstracts domestic or international, nor to policy and strategy, nor would you want me to: I can only speak to concrete and observable entities such as I perceive them. Is it in the American character, not to follow, but to lead?

With the not insignificant exception of the Native American Indians and most of the black population, America is comprised of the descendants of men and women who at some point over the last three hundred years or so wanted to improve their lives. They left their miserable shtetls and peasant hovels and urban slums and blighted potato fields and sailed the Atlantic. ‘We can do better,’ they said as one. ‘Sod Europe.’ They were animated by a restless desire to move on and make something of their lives. We can do better. A belief in improvability is written into the gene pool of their descendants, today’s Americans. Belief itself is imprinted there. Eugenics may be a discredited science, in fact it is not a science at all, but I think even if one cannot accurately isolate and calibrate the physical genetic difference between those Europeans who chose to move and those who chose to stay, one can state with some assurance that whatever the genotype at least the characteristics of the cultural and social phenotype are distinctive. Itchy feet. Ambition. Improvability. Belief. We Europeans, on the other hand, we are descended from those who said, ‘Oh well, could be worse, I suppose. Not getting into one of those nasty ships and going to a new world. Typical of uppity cousin Frank to think he can just march off and start again. Who does he think he is?’

Anyone who has visited an American bookshop will know that far and away the biggest section is devoted to self-help and the literature of Improvability across business, health, psychotherapy, dieting and love life. From How To Win Friends and Influence People, by way of 10 Things They Didn’t Teach Chicken Soup for Martian Men Without Tears it has grown into a genre worth billions. I will readily admit that the virus has reached our shores and that the shelving real estate devoted to this kind of literature is increasing year by year in British bookstores too, but it is quite clearly a US phenomenon and represents a deep part of the American belief that there is a technique to everything, that anyone and everyone can improve. Preaching is imprinted into the cultural DNA too. All this suggests a, to me, intriguing, historical and theological connection between America and certain protestant precepts of preaching and biblical exegesis and doctrines of improvability and works as opposed to the Higher Church, Anglo-catholic and Romish practices of ritual and ceremony and doctrines of original sin and submission. Politically this translates into the uncontroversial, I hope, conclusion that America was a Whig creation, not a Tory. Of course Whiggism per se no longer exists as a political force and Tories might, at first glance, think themselves the natural progenitors of America, for the word Tory is now associated with a belief in free markets and a dislike of big government, principles that strike an obvious chord across the Atlantic. But Tory, as I’m sure you know, originally referred to factions of Romish and high Anglican Jacobites with a distinct belief in the divine right of kings and a loathing of that entirely Protestant and Whig project, the Glorious Revolution and its 1689 Bill of Rights. With its phrases about ‘cruel and unusual punishment’, its insistence on the Commons and Lords having the right over the sovereign to raise money to fight wars, its reaffirmation of Magna Carta with a new emphasis on an independent judiciary – with all that, the text of the Bill of Rights reads like a rough draft of the American Constitution. Indeed throughout the document you could take the words ‘King’ and ‘Parliament’ and substitute them with the words ‘President’ and ‘Congress’ and you would swear it was the US Constitution you were reading.

So a nation founded politically on seventeenth century early Whig principles, as well as on those of Locke and then of Voltaire and Tom Payne. Founded somewhere on the broad spectrum of Protestantism: from the infrared of doctrinally mild churchmanship at one end to Puritanism, Levellers, Shakers, Quakers and various ultraviolet shades of dissenting sect at the other. The enlightenment, a work ethic, a belief in improvability, a reluctance to bow the knee to hierarchical authorities. Empiricism, rationalism and improvability working together as seen in the life and works of Franklin and Jefferson, the pursuit of happiness, a mission of self-amelioration and moving on, Manifest Destiny, the pioneer and the frontiersman, Horace Greely’s famous ‘Go West, Young Man’ and the railway barons and millionaires and financiers. The Almighty Dollar was born.

But the culture and literature of self-help and improvability is riddled with contradictions. On the one hand such books claim to release and empower, and on the other they promise a solution, a technique, a methodology that must be followed, adhered to, obeyed. Americans flock to these manuals and courses out of what seems to us a propensity not to lead or to think for themselves but precisely the opposite, from a naïve, trusting propensity to follow that would be charming in its ingenuousness if it did not strike us as so gullible in its credulity. The solutions and methodologies contained in the wiseacre effusions of these repulsive life coaches are usually reducible to that very American precept: “If life gives you lemons, make lemonade”. This could almost be the very motto of the United States. It seems so perfect, so ingenious, so satisfying. To understand its full meaning you have first to be aware that ‘lemonade’ to an American represents more than just a drink: according to the pleasingly cosy mythology of small-town America a child’s first experience of the enterprise economy traditionally comes when they set up a lemonade stand in the road outside their house. You and I might have made a cake for the village fete or raised pennies for the guy, but Bart and Lisa will set up a lemonade stall at which kindly disposed adults stop and spend a few quarters, nodding their heads in benevolent approval at the reassuring signs of good old American entrepreneurialism in the next generation. So – ‘when life gives you lemons, make lemonade’ is not just a way of saying make the best of a bad job, it is really a call to enterprise, initiative, self-help and finding ways to transform a disappointment into a dollar. Turn a problem into a challenge, a challenge into an opportunity, blah-di-blah di-blah. Welcome to the world of the business self-help book and life coach course, the world of observations so bowel-shatteringly trite, so arse-paralysingly obvious, so ball-bouncingly commonplace they make your nose bleed. A world where banality, venality and cracker barrel philosophising combine with outrageous pseudo-science, greasy false promises and grotesque opportunism. Business and lifestyle books of this nature synthesise the Phineas T. Barnum snake-oil huckster on the one hand and the Elmer Gantry homiletic exegete on the other. For the protestant tradition is one of adherence to the text. For the religious that text is the thumped bible that promises riches stored up in heaven, for the mercantile it is a book that promises riches stored up on earth. Conveniently these days, the bible thumpers happily square their circle and manage to offer riches in both realms, despite what would appear to be a repeated and unequivocal insistence against such a possibility by their religion’s founder. In either case to the outside observer it looks like a case of one being born every minute … Maybe that goes back to the gene pool too. The need to believe in self-improvement, in moving on, was likely to involve a belief in the guy who could sell you tickets for your passage to America along with promises that you’ll be met at the quayside, given a job, land and prosperity. In North Dakota for example, not the most prepossessing of America’s territories, they changed the name of the state capital to Bismarck in order to attract over German farmers, who came lured by the prospect of paradise and found an all but barren land that gets to 30 below in winter and up to the 100s in summer. The neighbouring South Dakota at least has the badlands and the Black Hills. North Dakota is so bad it hasn’t even got badlands. Yet Fritz and Otto were suckered into sinking their all in there and their descendants to this day till the same scanty and unforgiving soil. Sometimes belief means credulity, sometimes an expression of faith and hope which even the most sceptical atheist such as myself cannot but find inspiring. ‘I have a dream’ is the refrain of the most famous American speech of the last hundred years. Martin Luther King’s chorus is perhaps the signature American credo. And credo, of course means ‘I believe’, for it might be fair to suggest that Americans say ‘believe’ when really they mean ‘hope’ or ‘dream’. At any rate belief is imprinted into the phenotype, sometimes as I say inspirationally, sometimes to that point of credulity where wishing defeats reason.

You might argue then that America is not only a gene pool of adventurers, idealists and go-getters but also a gene pool of saps. A 18th century cant word for a con artist was a sharp (as in cardsharp) while the suckers and the gulls were called flats. The still sad sweet music of American humanity is full of accidentals you might say – full of sharps and flats. The tradition of con artist, grifter and schemer continues to this day up to that prize exhibit of peculation and malversation, Bernie Madoff as in ‘Bernie Madoff his cap as much as he likes, but Bernie Madoff with our money.’

But you can only con – it is an absolute rule of fraudulence – someone who wants something. Cons are about presenting opportunities, building castles in the air with words, offering visions of gold: in the case of Joseph Smith and the founding of Mormonism, literal gold in the form of inscribed gold plates delivered from heaven to an improbable address in New England. The more staggeringly absurd the promise the more likely, it seems, are you to find Americans willing to believe it. But the point is, if you don’t want for anything, you can’t be conned. And all Americans want for something. It is in that restless, insatiable DNA. It drives their capitalism and it defines their hopeful, confident can-do spirit of idealism and improvement as well as their belief that answers to life’s financial and spiritual impoverishments can be written down in a book. The very openness and optimism we love about Americans has a credulous and gullible obverse side. And maybe the things we routinely despise about ourselves as Britons, our scepticism, cynicism, doubt, pessimism, miserablism and suspicion – maybe they have a positive obverse. Empiricism, the great quality, the great and especially British quality, that fired the Enlightenment is essentially predicated on distrust. It distrusts convention, it distrusts revealed divine texts and it even distrusts reason (Newton famously aced the rationalist Pascal over the theory of light and optics by taking a piece of card and piercing a hole in it – something few continental intellectuals would deign to do). So perhaps our grumpy British fatalism and reluctance to trust or believe is not wholly to be deprecated after all, unattractive as it undoubtedly is.

Now in case this is sounding like an attack on American values and traits, let me say that my love, admiration and fascination remains intact. I am taking a line for a walk, I am playing with ideas here, not denouncing America and America’s characteristics, but delineating them as I see them from my wholly secular and idiosyncratic pulpit, this lectern.

But let me risk further strictures on American style by returning to what for me is the real lesson to be learned about America from that popular dictum about turning lemons into lemonade … let me illustrate my point with a story.

I was filming around Bilbao and environs in Northern Spain some years ago. The cast of our film was invited to the San Sebastian Film Festival premiere of a new Polanski movie called The Ninth Gate, not one of dear Roman’s best, but perfectly enjoyable and always a pleasure to be in St. Sebastian, or ‘Donostia’ as the Basques call it. I won’t go into the plot of the film, perhaps you know it anyway: suffice to say Johnny Depp plays an art dealer who gets involved in some sort of satanic Hammer House of Horror brouhaha or other. The opening reel takes place in New York (not filmed there of course: Mr Polanski can’t go to America) and there is a scene where Johnny Depp’s character arrives at his apartment, goes to the fridge, takes a pizza box from the freezer section, removes a frozen pizza and pops it into the microwave. Cue howls of laughter from the audience. I am sitting one row behind Johnny Depp and can see that he is rather perplexed by these helpless gales of Hispanic merriment and I hear him whisper to the Festival Director next to him, “Why are they laughing?” to which the Spaniard replies, wiping tears from his own eyes, “Because they cannot believe that anyone would do that to their stomach!” Genuine perplexity on both sides. An American thinks: why would anyone find placing a frozen ready-made pizza inside a microwave amusing? – a Spaniard, especially a Basque, whose cuisine is exceptional, thinks: why would anyone, above all somebody cultured and prosperous, insult their digestion with such complete rubbish?

So let me look again at that holy text: ‘if life gives you lemons, make lemonade.’ Huh? But… but… Lemons are amongst the best and most wonderful gifts of nature. They are adaptable, versatile and delicious. A slice for your gin and tonic – juice to zing life into salads, stews, fish and seafood. Oil and sweetness from the rind and zest that is pure and perfumed and precious. They are a staple of what doctors agree is the best dietary regimen we can follow. So if life gives you lemons, shout ‘Thank you, Life, thank you!’ But the American response is ‘make lemonade’ in other words – just add sugar and sell it.

Add sugar and sell it. This can be translated across into culture, can it not? When life gives you folk literature, gothic fairy tales and myth, what does Disney do? Add sugar and sell it. When the body of world art and tradition gives you complexity, ambiguity and difficulty – add sugar. When news and events present obstacles, problems and conflict – add sugar. For America sugar is an unalloyed good in and of itself and as a metaphor, a symbol. It might seem that Americans have the taste buds and desires of children. We know this from their popular foodstuffs: melted cheese, fried chicken, milk-shakes, cookies, candy, fizzy sugared drinks, pappy hamburgers smothered in sugared sauce – even their so-called high-end coffee is flavoured with sweet vanilla, cinnamon or hazelnut. Adults are helped to stay childish though sport, games, gadgets, monster-trucks and escapist movies, cowboys, superheroes, comic book villains and thrilling science fiction. Homer Simpson or Peter Griffin from Family Guy, are lovable forgivable funny and charming inasmuch as they are children. It’s all about how many cup-holders their cars have, nothing to do with suspension or engine, it’s all about feeding their stomachs and their minds with things that are sweet and easily assimilated: non-complex carbohydrates and non-complex concepts. It is no accident that in Family Guy, which if you haven’t seen you really must, the most memorable and popular character is Stewie, a sinister and malevolent babe in arms who is funny because he is entirely adult and sophisticated – and to prove it he has an English accent. He is sceptical about everything where his family is credulous about everything, melancholy where they are pointlessly breezy, direct and secretive where they are euphemistic and lacking in mystery.

While American women might seem less infantile, I think the cultural, social and indeed culinary influence of men allows me to make the generalisations I have. The little girl pageants, the underarm and leg shaving, the depilation and waxing to the point of Brazilian glabrousness of the American female, they certainly contrast with Mediterranean women’s ideals and suggest an infantilising purpose which is perhaps a little troubling. At all events all these are outward and visible signs of inward and invisible properties.

Professor Gomes of Harvard, a black, Baptist, republican, gay theologian told me once: “Americans don’t like solutions that are difficult, complex or ambiguous. If you can’t explain it in terms of good and bad they will not want to know. That is why most of them cannot accept evolutionary theory and why other nations and their systems are viewed as either good or bad, friend or foe.” It was interesting to hear from an American. It made me think that while the monochrome Britain I grew up may have been drab, it perhaps at least inculcated an ability to discern shades of grey. Shades of grey were all we had, we became expert at reading them.

It sounds as if I am building up a rather damning case against America. A land of infantile suckers. Suckers of sugar and suckers who follow every purveyor of snake oil and paradise. Leaders? Far from it. Followers. At worst vulgar simpletons, at best children.

Well, I count myself one of those suckers for at least 50% of the time. I love dumb action movies, and sentimental weepies. I love hamburgers smothered in sweet tangy sauce. I love toys and games and theme parks and RVs and spectacle and simple solutions. I love having my vulgar glands and cheap sensation receptors tweaked and tickled. I love believing in promises of a brighter future. I love the idea that training myself to breathe only through my nose or to chew my food 48 times before swallowing will make me thinner, less stressed and sleep better or whatever the latest fad might be. I love the idea that five simple mantras chanted twice a day might help me concentrate, make love more satisfyingly and become richer or that by following Jesus or Anthony Robbins will make me rich and happy.

For at least 50% of the time.

But for the rest of the time I want the truth. I want it unsweetened. I want to wash my mouth free of all sweeteners. I want to test all claims and statements on the anvil of experience or by empirical double blind randomised cohorts according to best scientific practice. I want to doubt, to experience, to think, to challenge and to scoff. I want art and literature and cinema and music that rejects easy pappy, poppy formulae and which reflects the truth of experience and all the ambiguities and complexities of existence. I want not sweet but bitter and sour and salt. I want realism not idealism. I want facts not fancies. I want imagination not wishing upon a star. I want learning, language and literature not philistinism, fantasy and infantilism.

Plato bade us imagine a creation myth that supposes an originally single sex human species that was split into two genders that are doomed forever to seek each other out and attempt to reunite into that original, atavistic unisex entity. Perhaps we should think of Western civilisation as having undergone a similar schism. Once we Europeans were one: 50 percent childlike, optimistic, open, innocent, credulous, dupable, fervent in believing in improvability and in systematic answers to life’s problems and the other half adult, sophisticated, worldly, pessimistic, suspicious and sceptical – distrustful of panaceas and pulpits and with a taste for darker flavours and more adult pursuits. The optimistic, go-getting, trusting, hopeful, childlike and credulous half upped-sticks and sailed for a New World, leaving behind in the old one only the stuck-in-the-mud, doubting, adult half. We have yearned for each other, without daring to admit it, ever since. America has longed for the sophistication, history and adult wisdom of Europe and Europe has pined for the childlike sweetness, instant fun and optimistic self-belief of America. The Yes We Can of Obama crystallised that quality into a battle cry which resonated just as much with us here in Europe, where we are tired of our own countervailing battle moan of “It’ll Never Work: not a chance. Forget it. What’s the point?”

When one talks of national characteristics one always leaves oneself open to ridicule. Am I claiming that there are no sophisticated Americans? Gourmandising, discerning Americans who despise sugar and sentiment? American pessimists and sceptics? Of course there are. I repeat an earlier asseveration: there is nothing you can say about America whose opposite is not also just as true. That is part of the allure of the place to me. And conversely, surely there are vulgar, obese, gullible, infantile Europeans? I don’t need to ask the question. None such in this lecture theatre of course. Well, two perhaps. Okay, three…

You know, I’ve a pet theory that none of this will matter in ten or twenty years, for America is almost certain in my unreliable view to be plunged into a cataclysmic and catastrophic civil war by then, one from which it may not properly recover for decades.

No, this internecine conflict I am picturing will not be fought over ideologies. It will not be a war of left versus right, religious versus secular, rich versus poor – nor of race or sect, nor white versus black, Christian versus Moslem, nothing like that. No, my visit to America showed me that the real tension will come as state declares war on state over … water. Who takes how much water from upstream of which river that runs through which states, who dams and reservoirs and controls the waters, these are the questions that will count. Utah against Arizona, Texas against Oklahoma, Colorado against California, Tennessee against Kentucky (I may even have to use my colonelcy and fight for Kentucky after all). Believe me, water will be a greater casus belli than abortion, gay marriage, global warming, race and the economy all rolled into one. The silver ribbon of time that is the Colorado River has still a bestarring role to beplay… but that’s another story and another lecture from someone who knows much more about these things than I do.

I’ve pointed out before that when something shocking, amazing, eccentric, wild, weird or unpredictable happens over there, you will often hear the amused and proud phrase, ‘Sheesh! Only in America!’ If you were to hear a Briton say ‘Tch! only in Britain!’ I think we can agree that it would almost certainly refer to something that was either predictable, miserable, oppressive, dull, bureaucratic, queuey, damp, spoil-sporty or incompetent – or usually a deadening mixture of all of those. Americans are constantly being surprised by their own country. We are constantly having our worst fears confirmed about ours. Literally this afternoon I was chatting to a courier who delivered some books to my house and we bantered back and forth about the coming cricket tours of the West Indies and the Australians.

‘There’s a chance Australia will lose, I suppose,’ said the courier. ‘After all they somehow did in 2003.’

‘Hang on,’ I said, nettled. ‘What do you mean Australia might lose? Don’t you mean England might win?’

‘England win? I don’t think we can go that far,’ he said. ‘England win!’ he left shaking his head and chuckling.

That’s Britain: we can’t win. We just have to hope the other guys lose.

Would I live in America? In a heartbeat. Would I miss Britain? No, for I’d take it with me, bag and baggage, scrip and scrippage, attitude and affect, manner and mannerism. I couldn’t not.

Finally then, as a lover of empiricism and passionate advocate of the fruits of the enlightenment I confess that it worries me that, despite President Obama’s commitment to science, his statement ‘I believe it is not in [the] … American character, to follow – but to lead’ might more accurately have been phrased: ‘I believe it is in the American character to lead the world in our willingness to follow. To follow anything be it never so trite, simplistic, irrational or incredible.’ But then perhaps we British lead the world in our unwillingness to follow anything, be it never so appealing, beguiling or bright with possibility.

Ah well. I am not sure we have arrived at any resolute certainties this evening. If you have not enjoyed or agreed with what I have said, well you can just – add sugar.

© Stephen Fry 2009